Roll for Initiative: The Adventuring Party as a Model for Silo-Breaking

Anytime it comes to explaining my super-nebulous, barely-legible career to a person who isn’t already an expert in the field(s) I traverse, I tend to start with an anecdote about how products/services sometimes (often?) suck.

Products and services can suck in all kinds of ways, both boring and interesting, but why they suck more often than not comes down to the fact that the people making them are operating in silos. If you work in a big organization, you probably not only know that truth but also feel that truth in your bones. If the word “silo” only conjures for you fields of golden prairie grains swaying in the wind: silos are the real and imagined barriers preventing different teams in an organization from properly syncing up what they say, do, and make. It’s often a tasty snack mix of org structure, politics, and force of habit. Finance doesn’t talk to Engineering doesn’t talk to HR doesn’t talk to Product etc. and so a moderately-complex product or service fails to deliver. In most big orgs today you’ll find the spores and colonies of a handful of different disciplines that hold ‘breaking down silos’ among their objectives, deriving from IT, design, organizational behaviour, and so on.

In this post, I’d like to wrangle a bit with what I’ve found to be a core part of many of these efforts: the cross-functional team.

The cross-functional team is, typically, a group of folks that meet regularly around a project or service to help steer and apportion the work to be done. They are, in most cases, an improvement over the typical status quo: black box, opaque, disconnected development efforts that shatter on contact with reality.

But: their size and sprawl can be challenging. You’re sometimes looking at a kind of United Nations approach, going down the list of possibly-impacted functions and making sure that everyone has a seat at the table. In a recent kick-off I attended, there were close to fifty attendees, with multiple kinds of overlap and close to 30 folks invited to and attending the regular workshops that followed.

As a comorbidity with the sheer size of the thing1 you might wind up with poor role definition, a rotating cast of players, passive ingestion rather than action-oriented mindsets, and a well-intentioned but perhaps-misguided bias towards broad engagement at the expense of momentum.

Can we think of other ways? I’d like to propose… the D&D adventuring party. Let’s get there together!

First, here’s Dan Hon from spring 2022 on silos (emphases mine throughout the rest of this post!):

“There’s the bureaucracy of processing and operations on information which, you know, fine. That’s a workflow. People do things and then pass them on to the next person and then maybe they go around in circles a bit before being properly refined into a sort of “macro” data, that can be passed on to Analysis down the hall.

Then there’s the “what do we do to design better processes”, the whole “hey, for the entire job to be done, is the refinement team in the right place? Do we need to do refinement? Can we do refinement differently? What if the inputs change?”

Doing that requires the cross-silo thinking, which in theory is where a bunch of layers and layers of cross-silo middle management would work when they’re not just managing the processing and bureaucracy and implementation and performance of the data refinement.

But mostly (sorry middle managers), I’d reckon (citation needed) about 95% of those middle managers are only managing downwards and not really managing sideways. At least, not effectively. Because the sideways stuff is a different job and explicitly silo-breaking/reconfiguring.”

For me Dan’s notions of sidewaysness, silo-breaking, and reconfiguration are the interesting bits here. It’s not just about taking existing structures and plugging them together more densely (which is what a typical cross-functional team looks like); what I read in Dan’s post is that the real magic comes from stepping back and resetting the orienting frameworks for the group away from their inherited functional divisions. It’s about fundamentally re-viewing and resetting the ‘spatial’ arrangement of the organization.

That brings us to our first big leap here – stay with me! Let’s read a bit from Eyal Weizman, architectural theorist, on how the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) move through dense urban environments, in ways that avoid traps and destabilizes the status quo (with a not insignificant grain of salt!):

Walls, in the context of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, have lost something of their traditional conceptual simplicity and material fixity, so as to be rendered – on different scales and occasions – as flexible entities, responsive to changing political and security environments; as permeable elements, through which both resistance and security forces literally travel; and as transparent media, through which soldiers can now see and through which they can now shoot. The changing nature of walls thus transforms the built environment into a flexible ʻfrontier zoneʼ, temporary, contingent and never complete.

And:

the enemy interprets space in a traditional, classical manner, and I do not wish to obey this interpretation and fall into his traps. Not only do I not want to fall into his traps, I want to surprise him!

(But also, as a note of caution as we borrow from these ideas:

“Imagine it – youʼre sitting in your living room that you know so well, this is the room where the family watches TV together after the evening meal … And, suddenly, that wall disappears with a deafening roar, the room fills with dust and debris and through the wall pours one soldier after the other, screaming orders. You have no idea if theyʼre after you, if theyʼve come to take over your home, or if your house just lies on their route to somewhere else.”

Working horizontally is, by its very nature, destabilizing. I’m cautious about embracing the tactics of a controversial military organization uncritically, and hemmed and hawed about including this piece – but what’s vital here is the practice of reorientation as a way of operating in spaces of asymmetry and defensiveness.)

Weizman describes an emergent practice in the IDF where small squads are able to move sideways through space, avoiding fixed defenses. It’s not just sideways-ness here that’s interesting to me, but also the sense of seizing something, through subtle (and not-so-subtle) force and guile. Geoff Manaugh’s The Burglar’s Guide to the City talks about similar spatial manipulation to wicked ends. In the case of cross-functionality, we’re ultimately taking something from the organization that it reflexively doesn’t want to give up: coordination that runs against its natural grain, which it will throw up all manner of immune responses to stop if you’re not careful.

So, burglary, right? Next leap coming up: Dungeons and Dragons. In D&D, you roleplay as a member of a small team (the adventuring party!) working horizontally / against the grain of an elaborate structure that has in its nature to foil your attempts to wrest power and agency from its deepest recesses through gatekeepers and hidden traps – wait what? Oh yeah, you fight monsters to get treasure and rescue hapless nobles, too.

Justin Alexander has a great, gold, old post on ‘Jacquaying the dungeon’ – essentially, designing and playing in D&D’s imagined contexts in ways that assumes multi-pathing and creative exploration of the context:

Each group is actively making the dungeon their own. They can retreat, circle around, rush ahead, go back over old ground, poke around, sneak through, interrogate the locals for secret routes…

And:

[T]he railroad-like quality of the linear dungeon is not its only flaw. It eliminates true exploration (for the same reason that Lewis and Clark were explorers; whereas when I head down I-94 I am merely a driver). It can significantly inhibit the players’ ability to make meaningful strategic choices.

There’s another thing that I like about poking at D&D here, and Alexander hints at it with the notion of retreating, sneaking, etc. as ‘meaningful strategic choice’ – power asymmetry. By its very nature, silo-breaking is operating down the power gradient from incumbent institutional forces.

(For fun, here are the techniques of Jacquayed dungeon design that Alexander lists:

- Multiple entrances

- Loops

- Multiple level connections

- Discontinuous level connections

- Secret and unusual paths

- Sub-levels

- Divided levels

- Nested dungeons

- Minor elevation shifts

- Midpoint entry

- Non-euclidean geometry

- Extradimensional spaces

I would love to be able to start talking about organizational mazes as “non-euclidean”)

Okay, so where are we so far? We’re here:

- Truly breaking silos requires moving sideways through organizational space by reorienting and reconfiguring

- Taking a posture of reconfiguration and reorientation requires that you think tactically about the organization’s immune responses (gate keepers, traps)

- A small group with a mission to cut through walls and Jacquay the organization might be more effective than a blobby team assembled along the very same functional lines it aims to cross

Now let’s hear from Matt Webb, in a post on avatars in collaborative work:

I wonder whether work (job work or creative work or whatever) would be easier if we leant into the larping aspect.

What if Google Docs, Figma, Slack, and all the other apps of the modern workplace were built around the idea that we were adopting a character and doing improv? Like, we have roles at old-school work, and I think that helps? Maybe we should have characters in software too?

Maybe locking ourselves into a single identity that remains fixed for all our time with a particular team and a particular app is a kind of mental straitjacket somehow.

I’m reminded of the way that the four ghosts in Pac-Man embody four different algorithms – they chase around the maze using: pursue; ambush; fake-outs; idling. You need them all!

What if, when I opened an app, I swiped in a different direction to consciously adopt a different character – a different personality algorithm. How would I collaborate on a doc as a healer versus a knight, or write email as a wizard versus a goblin?

Obviously in this case, Matt’s talking about a very specific kind of character – the “non-player character”, here enacted by a computer in the context of software. But I like his notion of LARPing in work, too: as we think about the work of working across functions, might we think actively, deliberately about roles?

For example, if we’re assembling a small team intended to work horizontally in Dan’s conception, where does it get us to think, tongue-in-cheek, using Matt’s character class ideas? What if we had an organizational adventuring party with a wizard (a data analyst, maybe, or designer/dev), a bard (a facilitator who can happily engage any SME you throw at them), a warlock (organizational consultant used to working with eldritch lich terrors – ELTs), and a cleric (a PM, perhaps, attentive to project and team wellbeing)?

This is a squad approach, oriented around the skillsets needed to traverse the organization, rather than a functional approach where we’re painting by number to try and get everyone in the room all at once.

Let’s think with Toby Shorin, Sam Hart, and Laura Lotti on squads for a sec:

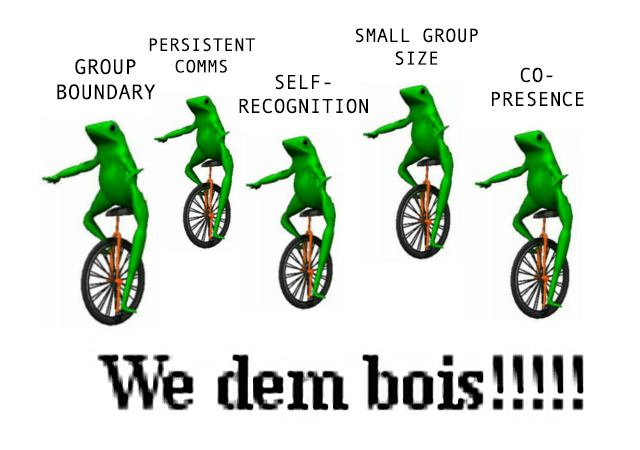

For the squad to understand itself as a whole, it maintains boundaries circumscribing strong group norms. Fuck a Dunbar number — the ideal squad count is no more than 12. How can you really be present with more than a dozen people? Small groups are crucial for tight coordination. A greater network may surround the squad, making it appear big and fuzzy from the outside. But for the core crew, an invisible circle binds and protects a space of group identity.

And:

Squad Wealth, from Other Internet

Squad Wealth, from Other Internet

Shorin, Hart, and Lotti aren’t necessarily thinking about a team within an organization per se, I don’t think – it’s clear both from this post and from their broader body of work that much of how they approach the world is perhaps… post-organizational? But maybe we can steal from this DNA a bit, inject it backwards into the legacy organizational structure, to think about semi-persistent squads of skilled practitioners, sitting across functional lines in terms of job titles but coming together around shared goals of horizontality in their organizations. Unconventional, perhaps-illegible boundary definition might be part and parcel of doing this well, too – in my case, as an indie consultant, I’m often one-foot-in-one-foot-out with teams like this, and it’s a strength rather than a weakness. There’s me (researcher/facilitator), a product manager over there, UX designer from another vendor, and a change management pro in Ops and together we move horizontally to open up new space of possibility in the org.

Let’s pull the threads together here and wrap this thing up:

- Organizations default to breaking silos by putting everyone together, which leads to project bloat and checking out

- Truly breaking silos requires moving sideways through organizational space by reorienting and reconfiguring

- Taking a posture of reconfiguration and reorientation requires that you think tactically about the organization’s immune responses (gate keepers, traps)

- A focused group – the adventuring party – with a mission to cut through walls and Jacquay the organization might be more effective than a blobby team assembled along the very same functional lines it aims to cross

- The adventuring party coalesces around skillsets (e.g. engagement across and up and down the org, ingestion and synthesis of signals, rapidly production of alternatives to the status quo), rather than coalescing along functional lines

- The adventuring party stays small, maintains persistent co-presence between projects and across hierarchies and functional lines, and works its extended network to pool knowledge and accelerate work

Lastly, just for fun, here’s what it feels like to enter a new organization as an indie consultant:

-

“Ringelman Effect: Members of a group become lazier as the size of their group increases. Based on the assumption that “someone else is probably taking care of that.”” From Collab Fund ↩